|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Japanese

Kendo is the traditional style of

Japanese fencing

and

dates back nearly two-hundred years. The definition of Kendo is

“way of the sword”. Kendo developed out of

Kenjutsu, the ancient style of

fencing. |

|

History.

Although the

Japanese sword is considered to be the most noble weapon, it

wasn’t always so. Until the 12th century,

archery was above the sword. It

only became the most noble after 1259, when Shogun Hojo Tokiyori restricted

swords only to nobles and members of the

warrior caste. From that time

onwards the sword became the badge of the warrior and surpassed the bow.

The

Japanese Samurai Sword was part of the warrior. It was even called the “soul”

of the warrior. Swords were believed to possess a life of their own, and

all kinds of characteristics were associated with sword, such as luck,

fertility and prosperity. The sole purpose of the sword was the eradication

of evil. Anger were not permitted when using the sword.

After the Mongol invasion(1274 and 1281), a weakness in the sword design was

discovered. The tip of the sword broke off, when chainmail and other hard

material was cut. The great swordsmith Goro Myudo Masamune eliminated this

by tempering and sharpening the blade all in one.

In the Nambokucho era (1336 –

1392). A split in the royal succession resulted in war and tyranny between

the Northern and Southern emperors. That is when the long sword (tachi),

was replaced by the shorter and lighter katana. The reason why the

modern warriors chose the katana was because of its diversity in

techniques. Lighter more agile weapons quickly dominated heavy long

weapons.

How did the Japanese develop such astounding and devastating techniques? It

all happened by a system of continuous learning. A warrior of proven

ability taught his techniques to other students of his school. These

schools existed for hundreds of years. The earliest recorded school was

found in 1350.

Duels were common place in ancient Japan. Warriors challenged each other on

a daily basis, with real weapons. Duels were also fought as a result of

family feuds, or as masters of honor. Honor played a huge role in ancient

samurai lifestyle. A slight brush of the scabbard against another person

was taken as an insult, and occasionally resulted in a duel. Even unarmed

civilians were struck down for such an insult.

Training was done with a real sword. This occasionally seemed to be too

hazardous, so patterns and forms, also called “katas” were planned

so that practice was harmless. Each kata focused on a particular

series of techniques. It was reported that the ono ha itto ryu

school practiced more than 100 katas! |

|

In the search for more realistic practice, the

bokuto (bokken)

or wooden sword was developed. This

allowed two people to train with techniques that were too dangerous to

practice with real swords. The bokuto did not replace the sword,

but it helped for a more realistic practice session. The bokuto

became more popular in duals – fatalities were reduced. It’s recorded that

the bokuto can be used as a dangerous weapon. The famous swordsman

Miyamoto Musashi killed many people with his wooden sword. |

|

|

Armour was introduced to during

the Edo period (1615 – 1868) in the form of padded iron-grid masks and

breastplates. The first breastplates were made from bamboo strips, sewn

into tough cloth. A wrist guard was also used.In the 19th century,

gauntlets replaced the wrist protection, and the breast plate transformed

into a wrap-around jacket. Modern armour replaced the padded jacket with a

solid breastplate, which covers the rib.

The Bogu consists of four different parts: Men, Do, Tare, and a pair of

Kote. Men is the helmet which protects the face, throat, top and sides of

the head. Do is similar to a breastplate and covers the chest and stomach.

Tare is the waste protector. Finally, Kote are like gauntlets and protect

the hands and wrists. The Bogu is worn over a Hakama (traditional Japanese

clothing) |

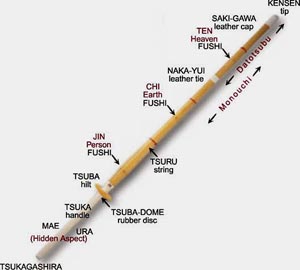

The ancient bokuto was replaced by

the lighter

shinai, made from

bamboo.

In 1876 a call for setting aside the sword was edict, but a year later the

Satsuma clan rebelled against the emperor. They were annihilated buy an

army with firearms, but they did not die in vain for they showed the value

of the martial spirit.

From that time on the decline in martial arts practice was halted and

training was introduced to schools and colleges. In the year 1912 the sport

Kendo eventually came into existence when all the various schools of fencing

came together and agreed to a set of rules for competition in armour and

with the bamboo sword. |

|

|

Present Day "Kendo"

Kendo practice takes place in a

dojo. The practitioners of Kendo must behave politely and

show respect to each other and the teacher. The Kendo uniform consists of a

jacket (gi), trousers (hakama) and a head towel

(tenugui).

Kendo practitioners stand

about 3 meters apart from each other, holding the shinais in their

left hands. The left thumb locks over the finger guard, and they move in

unison. Both sink to their haunches while withdrawing the shinais.

The right hand grips the shinai just below the finger guard and the

left grips the lower part. Both partners then stand and each steps

backwards half a pace with the left leg. The shinai lies in the

middle position, with its point at chest height.

Weight is distributed evenly on the feet, so movement can be made quick in

any direction. The feet skim over the ground and distance is adjusted

either by stepping, or by taking half a pace forward with the right foot,

then closing up with the left. When moving backwards, the left foot draws

back first and the front follows. The correct distance between fencers is

when the tips of their shinais are just crossing. The scoring

areas of the head, arms and body are struck with a cutting action, except

for the throat, which is attacked by a straight thrust. Cuts to the head

are the most frequently used technique. They are made by raising the sword

above the head and then brining it sharply down, using the shoulders as

pivots. The left hand brings the sword down and the right directs it. As

the sword passes vertical, the slightly bent elbows are straightened and as

impact is about to be made, the kendoka emits a piercing shout.

This is known as the kiai and it signifies resolve to strike

strongly. Whenever the opponent raises his shinai to a high

position, he exposed his mid section to attack. The defender holds his

shinai in the shoulder position. This makes for a shorter and faster

movement. Sliding the left hand up to the right during the cut provides

extra acceleration. The opponent’s wrist will become vulnerable if his

sword is held at a slight angle. The defender pulls back his sword from the

chudan kamae to an upright position, then he glides forward and

cuts across the exposed wrist.

Thrusts are made with the hands twisting inwards, or outwards during the

execution. Most of the force is developed by sliding forward with stiffened

elbows. The thrust either drives diagonally upwards into the throat, or it

travels horizontally.

As a beginner you can expect around six

months of training without armour. You will learn the basics of footwork,

posture, ki-ai (showing your spirit by shouting) and cutting. You

will practise these basics with other beginners and you will be allowed to

cut seniors who are wearing armour. Many people find this period of training

empowering. Shy characters learn how to move with confidence and how to make

an opponent feel their presence. More outgoing people learn how to control

their power and aggression.

Once you are in armour yourself, you will

learn a lot more about your emotions. You will encounter fear, doubt,

hesitation, anger and confusion. You will also learn to conquer them. Kendo

can be at the same time a very rewarding and very humbling experience. After

a relatively short time you will have the opportunity to fight anyone as

kendo does not separate genders, grades or weight classes. This also means

that you will fight people with much greater experience and skills than

yourself. Each and every fight will be a learning experience. |

|

|

|

Targets

In Kendo, there are four general areas to attack, subdivided into left

and right sides of the body - each worth one point. These are strokes to the

head, the wrist, torso, and a thrust to the throat. In order to be

considered successful, the attack is to be a coordination of the spirit,

proper usage of the sword, and correct movement of the body so that it would

be a clear and proper stroke, as if it were made with a real sword.

|

|

The

part above the temple of the head is considered as a point area. Generally

Men

is subdivided into three parts: Sho-men (center), Migi-men (right), and

Hidari-men (left). Tsuki is the throat area. Unlike other point areas, this

is the only one where the point is made by poking rather than by hitting.

Scoring Tsuki is allowed only for Dan players (black belts), since it

requires sophisticated techniques in order to score properly. |

|

|

Do

is subdivided into Migi-do (right) and Hidari-do (left). In general, Do

means the right one (i.e. the right side of the opponent). The left Do is

often described as Gyaku-do, which means the opposite Do. In olden times,

Samurai wore swords on the left side so it was difficult to cut that side,

since the swords could obstruct the blow. Therefore, in order to score on

the left Do, the stroke has to be especially precise. |

|

Kote

is subdivided into Migi-kote (right) and Hidari-kote (left). In general,

Kote means the right one (i.e. the right wriste of the opponent). However,

the left one is also considered as a valid point area if the opponent takes

an alternate posture in which the left hand is in front. |

|

|

Non Targets |

|

|

Tare is not considered

as a valid point area. The Tare is the protective equipment that protects

one's vital part! Don't hit or poke this part because it hurts!! |

|

|

Dogi

(jacket) is not considered as a point area. Dogi is a thick jacket made

of cotton and is dyed with indigo. They say that indigo has sterilizing

properties and a hemostatic effect. This is why working clothes in Japan

were traditionally dyed with indigo. |

|

Hakama (long pleated skirt) is not considered as a point area. By the way,

Hakama is a Japanese traditional clothing and its pleats have religious

meaning for the Japanese. The two pleats in the back derive from a verse of

a Japanese myth. According to this story, upon the national unification of

Japan, the two gods of war helped the god of the sun (the foremost among the

Japanese gods) and worked together to manage a nation using only their

dignity and without resorting to arms. Each pleat represents a god of war,

namely Take-Mikazuchi-no-Kami and Futsu-Nushi-no-Kami. The Koshi-ita, which

gathers the two pleats, represents the god of the sun, Amaterasu-Omikami. As

a whole, this represents the concept of Wa (harmony). On the other hand, the

five pleats in front represent the five principles which one has to hold,

that is, Jin (affection), Gi (righteousness), Rei (courtesy), Chi (wisdom),

and Shin (sincerity). |

|

How to fold the Hakama

|

How to fold the Dogi

|

|

|

|

|

|